by Caleb Knox

If you were to ask what people believe is the greatest threat facing our nation right now, you could expect a wide variety of answers. Among concerns of Coronavirus, gun violence or immigration, there would likely be mention of our national divides. Incoming research from political scientists is showing us that Americans no longer hold a shared sense of national identity. More than ever Republicans and Democrats view the other as being motivated by hate, while their party is motivated by love. This development, simply put, is not stable.

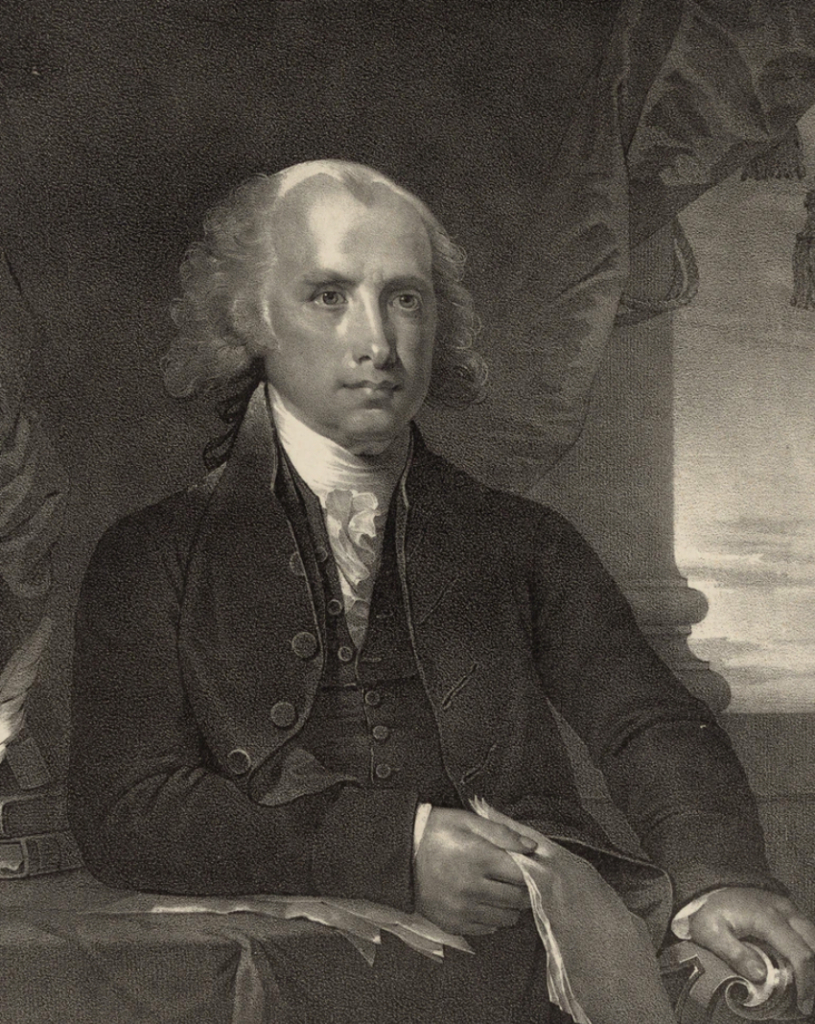

So what is pushing us toward hating each other? Although it can be tempting to see our current state of polarization as a more recent threat to our nation’s well being, the Founders were well aware of the dangers of rigid group identity. In Federalist 10 James Madison described his fear of “factions,” or for all intents and purposes, parties. He saw them as a hazardous part of human nature that “inflamed (people) with mutual animosity,” causing them to abandon any sense of the general welfare. To check this tribal intuition, Madison believed that the vast regional differences in the United States would slow the roll of divisive forces. So even if division “may kindle a flame within their particular States,” it would “be unable to spread… through the other States.”

To be sure, Madison’s defense has served us well. But he was writing in a time with established regional differences, when an outrage in Massachusetts was concentrated in Massachusetts, and division in Virginia was concentrated in Virginia. But what if this blockade were to wither away?

Social Psychologist Jonathan Haidt tells the story in an article titled “The Dark Psychology of Social Networks.” Beginning in 2004, a man by the name of Mark Zuckerburg would launch what we all know as Facebook, with the goal of making “the world more open and connected.” As noble as these intentions may be, nobody could foresee how this would play out in the political landscape. By making our “world more open and connected,” regional differences began to matter less and less. Polarizing forces that at one time would have been limited by geographical barriers, now have access to social media sites, and a much wider audience.

Despite widening the political conversation, the loss of regionalism is ripping us apart in the process. Political sparks of anger can now spread like wildfire as they are no longer bound by the local newspaper, but instead gain access to a global market of viewers on facebook, twitter and instagram, among others. Any idea, no matter how extreme, can now easily find an ally, but more importantly, it can now easily identify a common enemy.

These sites aren’t simply allowing this process of division and outrage, they are incentivising it. Social media sites indirectly make money by people spending time on their app, so these corporations spend a lot of time and money into developing algorithms, designed to show users content they agree with, and hide them from views which they disagree with. These falsified constructions of reality are known as echo chambers, where views contrary to the user can be blocked and taken off of their feed with ease. Algorithms grant a steady-stream of confirmation bias to those using their apps. This is crafting a generation who do not engage with ideas, but instead suppress them.

From the confines of social media, we are trading nuanced discourse for soundbites and 140-character tweets. Rather than promoting thoughtful discussions, debates, if they can even be called that, devolve into brief, ideological reductions. Consider a study from a group of social psychologists from 2017 who found that when tweets include demeaning and divisive words, they can expect to gain nearly 20% more engagement. The American experiment relies on an informed citizenry, but quick posts cannot plumb the depths of policy questions. So it becomes easier to post ideological jabs instead of expounding upon ideas.

A brief tweet can’t take into account individual complexities; instead online users group together and attack: “down with the patriarchy,” “own the libs.” When you abstract a portion of a population into a group stereotype they can be easily written off as unjust, someone you are morally justified to hate. It is more comfortable to hate a group from behind an anonymous screen, than to discourse with fellow citizens and neighbors in the public square.

Politics done right is a conversation, not a boxing match. Yet through social media the pay-per-view is available; opposing viewpoints are not seen as holding potential truths but a punch in the face. This trend runs against how our republic ought to function. Democracy is about disagreement, but you cannot constructively disagree with those that you have come to hate. By flattening regional differences, constructing positive feedback loops, and short- circuiting conversation, social media has led us to cross the rubicon from disagreement to disgust with one another.

Listening to the most recent Democratic Primary debate that took place in South Carolina, it is clear to see the effect that social media has had on our discourse. All the candidates, who within a week were mostly holding kumbaya hands behind Joe Biden, slung a slew of ad hominem attacks, instead of taking time to discuss the real issues at hand. As hatred has infiltrated our politics, it becomes clear the strategy: vilify the person, skip the idea.

Although there are many causes of our current political polarization, one thing is becoming abundantly clear – social media is fanning the flames of animus. My advice? Get off the grid. Just kidding… Although much of this will have to be solved through policy, don’t wait for D.C. Start in your own life. Look past the mirage of group identity and remember that the “others” are not the enemy. Making up the “faction” is a group of individuals each as complicated as you. So let’s disagree constructively, tolerate willingly, and remember the words of Christ and the warning of Lincoln, that “a house divided cannot stand.”